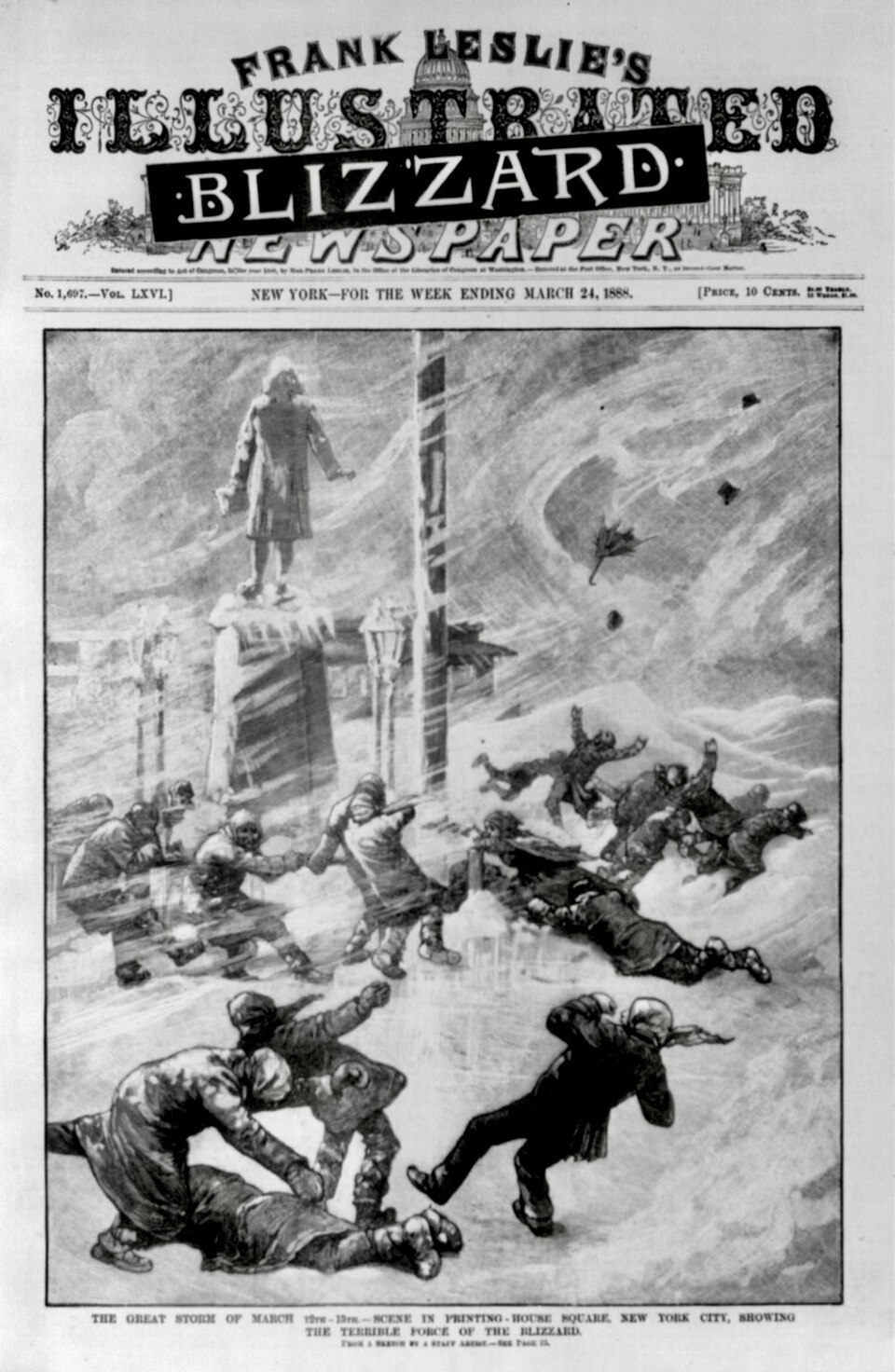

On March 11, 1888, the snow began to fall. The wind picked up. The blizzard lasted four days. My grandfather was 10 years old at the time, trapped in his farmhouse with his mother and sister. I read his account of the harrowing storm, as I was experiencing my own wild winter storm more than a century later in March of 2005…

Once Upon a Blizzard

As usual they were right, my wife, Dorothy, and my grown kids, Graham and Jenny. I’m stubborn, and I admit it!

“Be careful, Dad, you’re not 25 anymore.” Closer to 73 more like it. “George, if you fall… the new hip… this time of year there’s no one around to help you.” “The weather can be awful in March! Totally unpredictable.”

“I’m going anyway,” I barked back at them.

I had put this trip off twice to accommodate my platoon of MD’s. Now it was my time! Nothing comes between me and my beach.

Plus, I’d recently uncovered a latent interest. I’d discovered I loved to write, and I had ideas for two essays, what better place than our little cottage on Fire Island to develop them?

“Fine, have it your way,” my wife relented. “But take your cell phone at least, and make sure to keep it charged!”

Little did I know, that in a few days, I’d be caught in a major ice storm, out of food, cold and alone, wishing for once I’d listened.

Five generations in our family have enjoyed the rustic beauty, the serenity, the rejuvenating powers and quality of life that Fire Island affords.

My grandfather’s first house there was built in the town of Lonelyville in 1910. He was a very successful doctor and writer, who had published two books, including one that had been made into a movie written by William Faulkner and starring a young Mickey Rooney. Gramp and his wife had two daughters. Each married and had two sons. The 1938 hurricane carried the original house to sea, only the fireplace bricks and stones remaining. They rebuilt near the site in 1939 and named the house “La Casa del Perro.” (House of the dog, after their perennial pack of Labrador retrievers.) I was seven years old, my brother Ken was five. Our cousin, Tony Furgueson, was three; his brother, Mike, was still an infant. The third generation produced 12 great-grandchildren, and, so far, they’ve added 18 great-great-grandchildren. (With 2 more added since I originally wrote this piece!)

One house became four. “La Casa del Perro” is now nestled inland behind three bay front cottages, all owned by various family members. Lonelyville and the Great South Bay have always held me in a vise-like grip that tightens as the years go by. When I’m on the island, a calm comes over me that’s difficult to explain.

Saturday, March 5, 2005, 10:10a.m.: Rosie, our Heinz 57 dog, and I were sitting alone on the top deck of the Fire Island ferry to Fair Harbor, facing aft watching the sun reflecting off the shimmering ripples and dancing across the water. The gentle breeze made my skin tingle. The temperature was in the mid-40’s, as the mainland fell away in our wake.

Like settling into your favorite chair after a great meal, all tensions fading, warm thoughts of our late winter writing expedition became the focus. We landed and walked the third of a mile east to Lonelyville. Rosie on her leash, the supplies packed in two L.L. bean canvas bags secured to the two-wheel cart trundled behind me.

I had shopped for my own supplies (my wife, Dorothy, was busy and still more than a little miffed at me for insisting on going to the beach alone so early in the season). Un-chaperoned, I had skipped all dietary restraints, heading straight for the frozen pizza, frozen lasagna, cheese crackers, English muffins, Entemann’s hot cross buns and some canine treats for Rosie. Just the way I liked it, not a fresh fruit or vegetable in sight.

Patches of unmelted snow, graying and dirty, were still evident in shady spots left over from an earlier storm.

I opened the back door of the house, last closed in late December after a three-day visit. The air inside was dank and heavy, the shades drawn. The round, red and white thermometer in the living room registered 29 degrees. My new hip ached from the long walk and the biting cold.

The wake-up routine: Flip on the master switch in the electric panel box and engage the circuit breakers; turn on the wall heaters and chemical radiators; turn the stove on, the four top burners and the oven and open the oven door; hang blankets to block the front hall and stair well. The house was slowly waking from its hibernation!

Rosie and I walked down to the ocean. I sat on a bench overlooking the beach, as she moved in and out of clumps of beach grass, only her tail showing. The sun was warm. Could spring be coming early? I looked west to the lighthouse, then east to the jetties of Ocean Beach and beyond. There were no other people or dogs as far as I could see. For a moment, the feeling of invincibility the beach always gave me wavered. I pulled out the cell phone and decided to give home a call. No luck. Despite Dorothy’s reminder, I’d accidentally let the battery run dead.

It was a livable, 55 degrees inside, when we got back to the house. A quick check with the high command (I used the house phone.) “Are you having fun? Is Rosie eating? They say it may snow later in the week. Be careful! Call me later!” The earlier admonitions repeated.

I set up shop in the living room overlooking the bay and began to write.

Sunday and Monday, March 6, 7 and 8, the pattern was the same: up early, writing until lunch, then a walk to the beach and more writing.

That night, I checked the weather on Channel 5. The forecast had changed; snow was now predicted to start tomorrow. The weatherman also warned ominously of high winds. I’ll shoot for the 1:55pm boat back home the next day, I told myself. We should be on our way in plenty of time to avoid the storm.

The next morning, I packed my bags, checked the house for the last time and started for Fair Harbor, where we would board the ferry back to the mainland. Rosie and I got 200 yards or so from the house when the gray sky suddenly turned Wizard of Oz black. The wind changed direction on a dime – S.S.W. to N.N.E. For a few moments, a large calm area appeared between the bay in front of our house and West Island, about a half mile north.

The water was flat as a mill pond, eerily reflecting a single shaft of light that fought its way through the low clouds.

The wind picked up from the North. Sporadic gusts soon became a steady blast. The mill pond disappeared, replaced swiftly by rolling white-capped waves that began to pummel the shore line. The drizzle that had started earlier turned to rain. Rosie was shaking, never more than a few feet from me. We had gone only a short distance. I stopped. The rain changed to sleet and stung my face. The sleet quickly became hail. I tried to take a few steps forward, but slipped and nearly lost my footing. My hip throbbed. I edged over to the side of the boardwalk and held on to the base of a telephone pole to steady myself and rest.

Decision time: Maybe I should have paid more attention. Dorothy’s warnings rang in my ears. I realized then, Rosie and I couldn’t make it to the ferry dock. The walk was too icy, the distance to the boat too far. We retreated back to the house we had vacated moments before and threw the switches back on. I began to have second thoughts. Why didn’t I go home yesterday as planned? Why did I even come on this trip? And, then, other, more troubling concerns came to mind. What if the electricity goes out? What if I fall? Who’ll come and get me? Who’ll even know?

I called home again. Dorothy was relieved with my decision not to try and make it out. Rosie and I had enough food for one more day.

The snow and ice were now blowing parallel to the ground, rushing inland past the windows on the east and west sides of the house. The picture window was icing as the snow hit the warm pane, melted and immediately froze. The temperature outside dropped forty degrees in three hours. The temperature inside was holding at a comfortable 68 degrees. I crossed my fingers and hoped the electricity would stay on and the temperature would stay that way.

The wind was howling, blowing so hard that last year’s bull-rushes were blown flat, their puffy maroon-brown tasseled tops bobbing up and down repeatedly touching the ground, now rapidly turning white. The house shook so hard that the blankets I had hung to cover the hall entrance and stairwell flapped back and forth.

TV programming was interrupted with storm updates. I looked at the window. No lights on the bay or in any of the houses around me for miles.

A few hours later, early evening, Rosie was asleep on the well-cushioned wicker chair beside me, a warm throw around her, the edges tucked in loosely, with just her nose showing. My writing was complete. Dinner was over. One hot cross bun left for breakfast and a tin of dog food for Rosie, then our supplies would run out.

The book Gramp wrote about his colorful life, “Doctor On a Bicycle,” was on a side table. I hadn’t read it cover to cover since my Navy days, back in the late 50’s. I picked it up. The first chapter, The Keel is Laid, had always been my favorite. It recounts surviving the blizzard of 1888 as a 10-year old, stranded with his sister and widowed mother on their remote farm in Patchogue, a few miles from where I grew up and now live, on the mainland:

Chapter 1, The Keel is Laid from “Doctor On a Bicycle” by Dr. George S. King

“…It began softly on a Sunday in March – toward noon with little more than a thin gray drizzle. Three of us were at home, my widowed mother, my younger sister, Lotta, and I. My older sister, Alda, then 16, had gone to spend the night with a girlfriend.

“The morning had been clear, but when the rain began to fall, I heaped up some cordwood at the wood pile. Late afternoon in the waning light, I could see that the drizzle had become mixed with large, wet flakes of snow. For a time, I watched idly through the window pane, conscious of the comfort and warmth within. After a bit, I went outside and did my chores – fed the chickens, shut the chicken house and brought in a supply of coal and wood. Then we had supper.

“During the evening, the mercury plummeted as the wind howled out of the North. Lotta and I went to bed, but mother stayed awake listening to the blasts of wind that leaned hard against the house.”

I thought about their lives, no TV, no storm updates, no electricity, no telephone, and no one to check in with, just the three of them.

“During the night, the driven snow penetrated and drifted through cracks in the window frame. It covered my bed and spilled over onto the floor. In the morning, we wasted no time getting downstairs to the warm living room. I quickly made the kitchen fire. Then we found that a mounting snow drift had walled shut the west door of the kitchen, cutting our way off to the well. Undaunted, we turned to the east kitchen window, scooped up a wash boiler full of snow and set it on the stove to melt. After breakfast, we caulked the windows in my room to prevent snow from drifting in.”

Our modern double pane windows and insulation would have come in handy.

“Under Mother’s calm guidance, we worked smoothly and without panic, although we knew this was certainly a storm the like of which we had never seen before. During the day, the wind increased in volume. To keep the house warm, we shut off all the rooms except the kitchen and living room in which we had a large self-feeding coal stove with a heater pipe through the ceiling into Mother’s bedroom, the only heated room on the second floor. So fierce did the wind become that the carpet in the living room rose in billows.

“We moved the living room furniture to the most protected corner, behind the stove. Then with clothes horses and clotheslines, we draped off the corner and covered the carpet with rugs from other rooms to conserve heat.”

My reading was interrupted by flapping, banging sounds outside. I turned on the outside flood light. At first, I couldn’t figure it out. Pieces of wood were flying by the kitchen mixed with the snow and crashing into the boardwalk 15 feet away from the house. I finally realized what was happening. The lattice-work panels I had painstakingly nailed to the pilings that support the house were being torn apart, strip by strip, by the savage wind, propelling the slats like projectiles. There was nothing I could do about it. I went back and continued to read. I became a little edgy. The lights blinked off and on.

“One perilous trip to feed the chickens a pan of hot corn, the coop almost buried beneath a large drift. They huddled together and appeared quite happy. Indeed, when I next saw them three days later, the little flock were none the worse the wear for their confinement.

“But as I turned from the coop for the trip back to the house, the going was all but impossible. I was walking straight into the teeth of the storm. I made the woodshed and rested. The space between the shed and the summer kitchen formed a veritable wind tunnel, and the ground was a glaze of ice, swept clean of snow.

“The wire clothesline connecting the wood shed to the kitchen provided enough guidance to allow me to inch my way to the safety of the kitchen. Mother reached out and clutched my hand and together we entered the house, securing the door. Three days passed before it was opened again.

“We inventoried the food…”

Hard to imagine! There were no “Big Ben’s” or “A&P’s,” not even a “Stop ‘n Shop” back then.

“A barrel of flour, half a barrel of sugar, a firkin of butter, a big wedge of cheese and a barrel of newly salted pork. From the beams of the back kitchen hung sacks of homemade sausage, fresh hams well salted, a couple of smoked hams and several strips of bacon.

“On the floor stood crocks of pickles, chow chow laid the preceding fall, bags of home-cured dried apples, blackberries and dried corn – all the output of one woman’s hands. Buried in a pile of clean sand lay carrots, parsnips, cabbage and beets – all grown in our garden by me with the aid of the man who plowed the ground. A barrel of apples stood near the cellar door and on the floor was a firkin of salt fish – snappers and porgies – I had caught in the bay and cleaned. A layer of fish, a layer of salt – until the firkin was filled. Food was no problem.”

Their cupboard was a lot better stocked than mine. Their menu was a lot healthier. Cholesterol hadn’t even been invented yet.

“All we could do with the preparations complete was pass the time as pleasantly as possible. We read, we played Parcheesi, we listened as Mother read aloud from the Bible. We planned meals that would be unusual and we kept warm.

“In the afternoon, Mother made crullers, letting Lotta and me cut little figures from the dough to fry in the hot fat; men, dogs and horses. We made molasses taffy and pulled the dough into tasty sticks. Cut off from the world, we had a happy day. Just ourselves and Mother, so calm and unperturbed.

“The third day passed as had the first and second, the howling wind devils shrieking to each other from house corner and eaves. Occasionally with a rumbling roar, the snow would crash from the rook like an avalanche, covering a window.

“Going to bed became a ritual. I undressed in Mother’s room; that is, I took off my outer garments down to my woolen underwear and socks but no more. Then I put on my flannel night shirts. To help shut out the cold in my room where the temperature was below zero, we placed an extra feather bed as a coverlet upon my bed, although I already had one under my sheets.

“The one last thing before retiring, Mother asked us to kneel in prayer in her room. When bedtime came, it was fun to share my cozy featherbed with my lively fox terrier who nosed his way into the depths beside me.

“Abruptly the morning of the fourth day broke clear and cold, with only a gently breeze. The sun was unexpectedly warm. The melting snow froze hard at night. The next morning after seeing to my chickens, I put on my skates and sailed over fences, rode high on drifts and slid down valleys until at last the warming sun melted the crusted surface.

“Throughout those four days and nights, we went about our small tasks with a pleasurable sense of excitement. We moved through the wild, white days and icy nights warmed by our Mother’s calm and absolute assurance.”

I thought about the calls from Dorothy and the kids, nice to know that they were there.

“God was with us within the snowbound walls of our farmhouse. No harm could befall us. The winsomeness and courage flowed from Mother and have ever remained in my heart and mind!”

I looked over at Rosie sound asleep, her nose still showing through the throw around her.

Time for bed. I couldn’t stop thinking about the story I had just read. Some things never change. I let Rosie out the back door, now the lee side of the house. The wind, if anything, had strengthened. The house continued to shake. The drifts were piling up. Only two of the five steps leading down to the garden were still visible. Rosie all but disappeared as she went about her business. I toweled her off when she bounded back through the door and then put an extra duvet on the bed.

I sat and watched the storm out the window. The water roiled, erupting in angry white caps matching the gusting wind and snow in intensity. It was pitch black outside now, but from time to time, I could still see bits of wood and flotsam fly past the house. Thankfully, nothing had broken a window. Yet.

The lights flicked on and off again and then in an instant, the house went dark. I felt around for the flashlight I had left on the kitchen counter and the matches. I lit two candles and sat back to ponder my next step.

I could move from the bay cottage where I was now ensconced to the back house, “La Casa del Perro,” which had a working fireplace. But it was a 400 foot walk down an icy boardwalk in blizzard conditions and, with my bad hip, I couldn’t take the chance.

Another option: I could call Dorothy on my cell phone and see if someone with a 4-wheel drive could try and make it down the beach to get me. Candle in hand, I searched around for my coat and found my phone. You idiot, I told myself. I’d forgotten to recharge it.

Hip throbbing, I pulled myself upstairs and fumbled in the dark, retrieving three extra blankets from the blanket chest. I limped back and spread them over the bed, then settled in for a very long night.

The house was insulated, but without working heaters, the temperature began to fall. The portable, battery-operated radio gave periodic weather updates. The forecast called for snow throughout the night, the outlook for tomorrow was now, at best, uncertain.

I tried to sleep, but couldn’t. My hip ached, and I knew Dorothy and the kids would be beside themselves, since they couldn’t reach me on the landline or cell. I thought of all the storms I’d weathered as a kid, here at the beach and on the mainland, including the hurricanes of 1936 and 1938. I thought of all the rough nights at sea I’d experienced in the Navy. But despite all that, I admit I was more than a little scared.

It’s one thing to be caught in a storm while at sea with your shipmates or at home with your family. It’s another to be alone, over seventy, with a bum hip and no means of communication or provisions.

I decided to sit up for awhile. The news updates signaled no change. The temperature had dropped to the mid-teens, the wind gusting to 50 mph causing the snow to pile in huge drifts. Power outages were reported throughout Nassau and Suffolk.

Despite the extra blankets, I began to shiver. The house was bitterly cold now. Don’t panic, I told myself. The words from Gramp’s story came back to me…

“We moved through the wild, white days and icy nights warmed by our Mother’s calm and absolute assurance…

“The winsomeness and courage flowed from Mother and have ever remained in my heart and mind!”

Calm, absolute assurance and courage. If my widowed great-grandmother and her two small children could find the strength to weather a storm of such ferocity, surely so could I.

I thought of the three of them, alone and vulnerable, in their primitive farmhouse as I finally dozed off.

I woke up abruptly at 3:30am. The TV was blaring. Lights blazed throughout the house. The power had come back on.

I could see my breath in the house. Rosie refused to get out of bed. For some inexplicable reason, she had nuzzled under the blankets and was by my feet. She’d never done that before. Maybe there was some fox terrier in her, after all!

The floor was ice cold, I could feel it through my socks. I turned off the lights, adjusted the heater and radiator and jumped back into bed. I decided not to wake Dorothy, I’d ring her in the morning. Rosie and I slept through uninterrupted until 7:30.

When we woke, the wind had dropped. Snow covered everything. The beautiful white blanket was interrupted only by two sets of deer tracks. It was still – you could hear the quiet.

I called home. Dorothy picked up the phone on the first ring. “Why didn’t you call?” I explained. Just as I’d imagined, she and the kids had been extremely worried.

I duplicated the exiting routine of the day before. Rosie and I headed for the 1:55 boat. This time, we made it. Walking on the slick patches of snow and ice turned the trip into an adventure of its own. Normally a 20 minute walk, it took us well over an hour. All I could think of was falling on the new hip.

If I had not left the copy of Gramp’s book, “Doctor On a Bicycle” in plain sight on the living room table during my previous trip, I might never have gotten to know my Great-Grandmother, Grandfather and Aunt Lotta as well as I did that day. And, although I’m reluctant to admit it, I might not have gotten through that long, stormy night unscathed.

Sharing our adventures was an unexpected dividend. I never met my Great-Grandmother; she died two years before I was born. Reading about her made me realize that Rosie and I would have fit right in. She would have clucked over us just as she did with Gramp and Aunt Lotta.

Though one hundred and seventeen years separated our two storms, for several hours during that long night, I felt as though we were all in the same room, as though time had collapsed and different generations had touched one another.

Maybe somehow they had. My one-day blizzard, March 8, 2005 had occurred almost exactly to the date of their blizzard, March 11-14, 1888. Eerily ironic, Gramp was born March 8, 1878.

George S.K. Rider

9/10/07

Image Source: The Great Storm of March 1888 in Printing-House Square, New York City, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, published March 24, 1888. Public Domain.

Wow, Dad. I read “Blizzard” last night in the middle of the raging rain and wind storm here, with the power knocked out. Timing of your post was amazing!! xo Jenny